The seeds

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The long journey through the wheat supply chain, from seeds to pasta passing through the food commodities markets, has come to an end.

This final stage is a reflection on the hidden costs of this enormous and lengthy chain, in terms of health and its impact on the environment and communities: how much does the current agro-industrial system, through which we feed ourselves, impact? While it’s true that in the last century, this system has managed to produce enough food for a exponentially growing population, reducing the real price of food to make it more accessible to the poor and alleviate hunger, it’s also true that the current agro-industrial system has imposed huge environmental and health costs ranging from greenhouse gas emissions to soil degradation, from water and air pollution to overexploitation of aquifers, from loss of biodiversity to increasing antimicrobial resistance, persistent malnourishment or undernourishment, and rising obesity.

Wild plant purpose is not to nourish us but to spread their own seeds. How do they do so freely, in an oligopoly?

The ancient shared history of wheat and humanity, which began with the domestication of wild cereals by humans, continues today where it all began 11,000 years ago: in Mesopotamia. It may seem like a coincidence, but perhaps it isn’t.

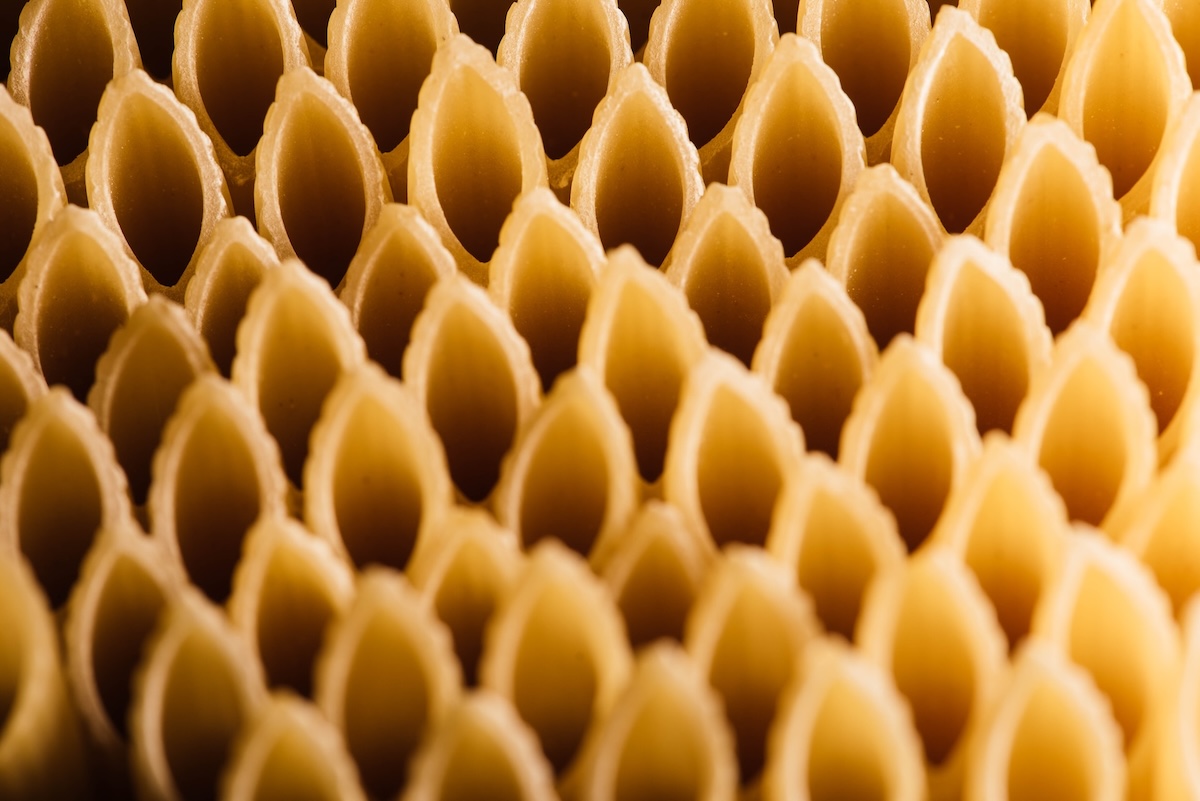

There is nothing similar in Nature, but our flours are increasingly standardized.

The notion that ‘yellow’ pasta is of good quality has now been dispelled. The opposite is true.

According to a report published in 2022 by the ETC Group, an independent research group focusing on agriculture and democratic control of technologies, “these food giants exploit workers, poison the soil and water, decrease biodiversity, and perpetuate a food system structured on economic and racial injustice.” Furthermore, reading some reports and investigations on deforestation, land grabbing, pollution, and the massive use of chemical synthetic products, one can realize the impacts of these agribusiness giants like Cargill, considered by Mighty Earth, an advocacy organization focused on nature protection, as the worst company in the world. A Global Witness investigation released in September 2023 also reveals that the food giant Cargill has been purchasing soybeans from various agricultural companies in Bolivia where, since 2017, over 20,000 hectares of forest have been cleared. The same has been reported by an article on Inside Climate News, stating that Cargill continues to fail in meeting commitments to eliminate deforestation from its supply chains.

Martien van Nieuwkoop, Global Director of the Agriculture and Food Global Practice sector at the World Bank, writes: “Environmental and health costs are not reflected in the current market prices of associated food products. According to our estimates, the negative impacts associated with the functioning of the current food system amount to at least $6 trillion.” He adds: “This is a conservative estimate, which only takes into account five ‘externalities’ of the current food system: malnutrition, food loss and waste, food security, land degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions resulting from current agricultural practices. There are likely substantial costs associated with other externalities that have not yet been considered.”

These include, for example, health costs related to mortality, the increase in non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, or the costs of unhealthy diets characterized by high salt consumption or low fruit intake, leading to premature deaths, as reported by the study “Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries”, which lasted 27 years and was published in the journal The Lancet in 2019.

In addition to these, there are the social costs of the climate crisis: forced migrations, extreme weather events, and poverty. The FAO’s annual report “Revealing the true cost of food to transform food systems” calculates that the health and environmental damages caused by the food industry cost $10 billion per year, which is 10% of the global GDP.

La segretezza dei trader è parte integrante del loro modello di business.

We all pay this cost. Some examples include the increase in diseases such as diabetes, linked to diet, and the consequent rise in taxes. Or the increase in food prices, caused by extreme weather events and inflation. Then there’s the standardization and homogenization of products: less biodiversity in the fields means less biodiversity on our plates. A 2013 study published in Food Research International shows that the absence of microorganisms in most agricultural soils, caused by the massive use of chemical synthetic products, and the use of hybrid seed varieties affect human health, starting with sensory perception and the ability to detect flavors and aromas. In other words, soils increasingly depleted of microorganisms impoverish the food we eat.

Obviously, the impact, the so-called costs or negative externalities, vary depending on one’s social class and whether one is a citizen of the global North or the global South. The FAO report shows that current food systems increase poverty in low-income countries: many farmers in the poorest countries do not benefit from the value of their products, often sold at low prices to traders and producers who make the greatest profit. Paradoxically, this means that farmers cannot afford nutritious diets. In reality, the same happens in the wealthy “global North”: the poor eat less and eat worse.

The current agricultural system based on commodified food and profit maximization operates only through an extractive and predatory logic, which drains energy, natural resources, and destroys the age-old knowledge of local communities. In producing our food, we effectively kill biodiversity, ecosystems, traditions, and cultures. The land is poisoned with pesticides, making it more sterile, and groundwater and air are polluted. All of this embodies and gives form to the idea of an “inert Nature,” to say it in the words of the Indian writer and anthropologist Amitav Ghosh.

A Nature to be subjugated.

The proposals are varied and very concrete. Among these: ensuring the right to healthy food by adopting social measures such as universal basic income; mandating governments to source food from local producers; introducing a lower VAT on products that meet certain criteria, such as social and environmental sustainability; taxing the windfall profits of multinational corporations; demanding greater transparency on raw materials, such as cereal storage; introducing stricter regulation in the futures market; halting trading when there is speculation and a drastic increase in prices; taxing shareholder dividends at higher rates.

But above all, as written by La Via Campesina, an international organization that coordinates peasants, small and medium-scale producers, indigenous communities, and rural women in Asia, Africa, America, and Europe:

However, to treat food as a common good and a human right, it is necessary to overcome the current economic system based solely and exclusively on profit maximization and “performance” as the sole value. If production increases, it matters little whether it comes at the expense of future resources or the health of the environment or people. If cutting down a forest increases production, no one measures in this calculation the loss involved in desertifying an area, destroying biodiversity, or increasing pollution. In other words, companies make profits by calculating and paying only a minimal portion of the costs.

The alternative is to transparently calculate the economic and social costs resulting from the use of environmental resources, so that they are not borne by other populations forced to migrate or by future generations. In conclusion, the value of food – as well as other raw materials – should be rebalanced because pasta produced in monoculture, using large quantities of chemical synthetic products, cannot cost just a few cents but should cost much more.

Conversely, those who produce pasta by caring for the soil, cultivating with agroecological methods, strengthening short supply chains, gender equity, and environmental health, should sell it at a lower price. Behind that pasta is not just a product; there is the care of ecosystems, the environment, and our health. And to put it broadly, it concerns the entire “Common Home,” of which we passing humans are a part.

This work was conceived and created by Sara Manisera, Bertha Foundation Fellow 2023, with the support of Bertha Foundation, and produced by Slow News.

Illustrations: Vito Manolo Roma

Un podcast settimanale per approfondire una cosa alla volta, con il tempo che ci vuole e senza data di scadenza.

È dedicata all’ADHD e alle neurodivergenze. Nasce dall’esperienza personale di Anna Castiglioni, esce ogni venerdì e ci trovi articoli, studi, approfondimenti, consigli pratici di esperte e esperti.

La cura Alberto Puliafito, è dedicata al giornalismo e alla comunicazione, esce ogni sabato e ci trovi analisi dei media, bandi, premi, formazione, corsi, offerte di lavoro selezionate, risorse e tanti strumenti.

La newsletter della domenica di Slow News. Contiene consigli di lettura, visione e ascolto che parlano dell’attualità ma che durano nel tempo.